Search Results

Publication Date

Military REACH Publications

Focus Terms

Military Branch of Service

Sample Affiliation

Age Group

Military Affiliation

Publication Type

Award Winning Publications

1.The role of program evaluation in keeping Army health “Army Strong”: Translating lessons learned into best practices

Authors

Year

2.An evaluation of seAp's military advocacy service: Early findings report

Authors

Year

3.Mental health evaluations of members of the Armed Forces

Authors

Year

4.Using marriage education to strengthen military families: Evaluation of the active military life skills program

Authors

Year

5.Handbook on impact evaluation: Quantitative methods and practices

Authors

Year

6.Evaluation of the Transition Assistance Program (TAP)

Authors

Year

7.Implementation and evaluation of a virtual skills-based dementia caregiver group intervention within a VA setting: A pilot study

Authors

Year

8.Program outcomes evaluation for 21st century North Carolina veterans experiencing reintegration problems

Authors

Year

9.Challenges and facilitators to building program evaluation capacity among community-based organizations

Authors

Year

10.Requirements for mental health evaluations of members of the Armed Forces

Authors

Year

11.Examining complex program adoption decision-making in a health pilot for U.S. women military veterans: A single revelatory case study

Authors

Year

12.'Motor Magic': Evaluation of a community capacity-building approach to supporting the development of preschool children (Part 2)

Authors

Year

13.Data quality in evaluation of an alcohol-related harm prevention program

Authors

Year

14.‘One is too many’ preventing self-harm and suicide in military veterans: A quantitative evaluation

Authors

Year

15.Comprehensive program evaluation for strengthening military mental readiness

Authors

Year

16.Dissemination and evaluation of marriage education in the Army

Authors

Year

17.A program evaluation of a recreation-based military family camp

Authors

Year

18.An ecosystem approach to the evaluation and impact analysis of heterogeneous preventive and/or early interventions projects for veterans and first responders in seven countries

Authors

Year

19.Continuing the mission: Findings from a needs assessment supporting the new generation of student veterans

Authors

Year

20.Evaluating moral injury in combat-deployed and non-combat military personnel

Authors

Year

Research summaries convey terminology used by the scientists who authored the original research article; some terminology may not align with the federal government's mandated language for certain constructs.

MILITARY FAMILY READINESS: AN OVERVIEW

HOME ABOUT MILITARY REACH LIBRARY UPDATES RESOURCES 12 APR 2024 MILITARY FAMILY READINESS: AN OVERVIEW By Emily Wright, Allison L. Tidwell, and Emily HansonEditors Kate Abbate You may have seen in a REACH publication, the news, or other forms of media the importance of military family readiness – but have you ever wondered what the phrase really means? In this article, we'll follow the fictional Stanley family as they navigate military life. Through these events we will explain what military family readiness is, how it influences family functioning, and what resources the military has created to promote military family readiness. What is military family readiness? The term readiness is commonly referred to throughout military culture in reference to Service members. The Department of Defense (DoD) defines readiness as "the ability of military forces to fight and meet the demands of assigned missions" (Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2017, p. 195). Blake Stanley is a 30-year-old active-duty Soldier preparing for deployment in one month – for Blake, readiness means that they are physically and mentally fit and ready to adapt during deployment. For their partner Sam and 4-year-old child Alex, though, readiness is much broader. Military family readiness differs from Service member readiness in that it is "the state of being prepared within the unique context of military service, to effectively navigate the challenges of daily living and military transitions" (Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, 2021, p. 54). Assessing military family readiness is not a matter of determining whether a family is "ready or not," but rather a matter of describing the family's capacity to handle the challenges they encounter. Therefore, military families need to have adequate means to overcome both military (e.g., relocation, deployment) and normative (e.g., parenting stress) stressors. Although Blake is physically and mentally prepared for deployment, they must navigate this upcoming transition with Sam and Alex as well. Currently, Blake and Sam share childcare tasks like daycare drop-offs and meal planning, as well as alternating planning date nights every week. When Blake is deployed for the next six months, Sam must now do all daycare drop-offs as well as grocery pick-ups and meal preparation. Because of the time difference, Blake will only be able to video call once a week at 10:00am, right in the middle of the workday. To adjust successfully as a family during deployment, Blake, Sam, and Alex will have to establish a new sense of "normal." Family scientists frequently gauge "readiness" by evaluating functioning across individual family members, family relationships, and life domains (Hawkins et al., 2018; see Figure 1). By capturing insight into these various aspects of family functioning, we can gain a holistic understanding of families' readiness to respond to stress and change. When determining what comprises family readiness, it is important to view the family as a group of interdependent members who are constantly influenced by each other. Thus, when one member of the family system or one area of the system is not at optimal functioning, the rest of the system may not function at its best. The stress of the upcoming deployment has led Blake to feel anxious, along with the rest of their family. Sam is worried about how to handle caring for Alex alone for the next 6 months. Alex has picked up on both of their parents' moods and has started crying more frequently due to the stress. To help ease everyone's stress, Sam plans a family picnic for the three of them to discuss communication expectations while Blake is gone and strategize how Alex can keep in touch with them. This comes as a relief to the family, as there is one less concern to worry about. Why does military family readiness matter? Military family readiness is a primary objective for the Department of Defense, as maintaining ready families ensures maintaining a ready defense force (Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, 2012). Spillover is a commonly cited concern for military family readiness; that is, issues at home may influence Service members' performance at work, while in other cases, issues at work may negatively affect family functioning (Escarda et al., 2022). For example, when couples encounter communication difficulties or marital conflict during deployment, the Service member may be distracted by their relationship issues and therefore less able to complete their military-related duties (Cater et al., 2015). Blake and Sam agree to prioritize video calls, and Sam coordinated with their boss to allow them to block one hour of their schedule as long as they can stay after an extra hour. They both look forward to the call every day, and it is a relief to have a scheduled and predictable time together to meet. Knowing when they can expect a call helps Blake focus on their deployment-related duties during the week. To ensure that Service members' capacity to perform their duties is not impeded by family-related issues, it is necessary for the Department of Defense to place an emphasis on military family readiness (Lester et al., 2011). Not only is family readiness important for ensuring that Service members are ready to perform their military duties, but it is also critical for the retention of Service members in the military. The decision made by many Service members to enter the military or to remain in the military is often determined by financial, social, and relational functioning. For instance, when families encounter work-family conflict due to family life stressors, like having multiple children or worrying about finances, they tend to report less satisfaction with military life and are therefore more likely to separate from the military (Woodall et al., 2023). After two weeks of longer workdays and having to ask the neighbor to pick up Alex from daycare, Sam starts to feel overwhelmed and asks Blake if they can reduce the number of 10am calls. Blake can't stop thinking about Sam's stress and starts to feel guilty about being gone for so long. This is their third deployment, and this happens every time. For the sake of their family, Blake wonders if it's just easier to leave the military. Indicators of Family Readiness Figure 1. Indicators of Family Readiness (Hawkins et al., 2018, p. ES-3) Promoting readiness through the Military Family Readiness System Family functioning and readiness is further supported through the Military Family Readiness System. The Department of Defense created the Military Family Readiness System to serve as a network of programs and services which promote military family well-being, readiness, resilience, and quality of life. Since the 10:00am call has been causing some tension, Sam and Blake decide to download the Love Every Day app to communicate and connect throughout the day. Sam decides to join their installation's Family Readiness Group to connect with other spouses and parents that have experienced the stress of deployment. When Blake is preparing to return home, the couple watches a webinar on family reunions to spark conversation about how to manage expectations. Although the deployment process was stressful for each family member, utilizing these resources helped the Stanley family cope with military and normative stressors, as well as help Blake feel confident with continuing their military career. RECENT STORIES Related Stories in References Escarda, M. G., Arroyo, Y. A., & Redondo, R. J. P. (2022). Work-family spillover in the Spanish armed forces. Community, Work & Family, 25(3), 374-388. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2020.1771284 Hawkins, S. A., Condon, A., Hawkins, J. N., Liu, K., Ramirez, Y. M., Nihill, M. M., & Tolins, J. (2018). What we know about military family readiness: Evidence from 2006-2017. Research Facilitation Laboratory Army Analytics Group, and Office of the Deputy Under Secretary of the Army. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1050341.pdf Joint Chiefs of Staff. (2017). DOD dictionary of military and associated terms. Department of Defense. https://www.tradoc.army.mil/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/AD1029823-DOD-Dictionary-of-Military-and-Associated-Terms-2017.pdf Lester, P., Leskin, G., Woodward, K., Saltzman, W., Nash, W., Mogil, C., Paley, B., & Beardslee, W. (2011). Wartime deployment and military children: Applying prevention science to enhance family resilience. In S. MacDermid Wadsworth & D. Riggs (Eds.), Risk and resilience in U.S. military families (pp. 149–173). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-7064-0_8 Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. (August 5, 2021). Military family readiness (DoD Instruction 1342.22). Department of Defense. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/documents/DD/issuances/dodi/134222p.pdf Woodall, K. A., Esquivel, A. P., Powell, T. M., Riviere, L. A., Amoroso, P. J., & Stander, V. A. (2023). Influence of family factors on service members' decisions to leave the military. Family Relations, 72(3), 1138-1157. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12757 MOBILIZING RESEARCH, PROMOTING FAMILY READINESS. Our Partners Auburn University University of Georgia Department of Defense US Department of Agriculture 203 Spidle Hall, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama 36849 Military REACH Department of Human Development and Family Sciences (334) 844-3299 MilitaryREACH@auburn.edu Contact Us Website Feedback Stay Connected with Military REACH These materials were developed as a result of a partnership funded by the Department of Defense (DoD) between the DoD's Office of Military Community and Family Policy and the U.S. Department of Agriculture/National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA/NIFA) through a grant/cooperative agreement with Auburn University. USDA/NIFA Award No. 2021-48710-35671. Last Update: March 2024 2017 - 2024 All Right Reserved - Military REACHPrivacy Statement| Accessibility Plan This website uses cookies to improve the browsing experience of our users. Please review Auburn University’s Privacy Statement for more information. Accept & Close

THEORY SERIES: FAMILY SYSTEMS THEORY IN A MILITARY CONTEXT

This month, Military REACH continues our Theory Series, where we break down the common frameworks family scientists use to better understand family experiences. Specifically, we will focus on Family Systems Theory (Kerr & Bowen, 1988). We will provide an overview of the model with examples from a vignette, connect it to military family experiences, and suggest how military families can use knowledge of Family Systems Theory to overcome the challenges they face. Family Systems Theory Overview Vignette: The 2002 Disney film Lilo and Stitch follows the adventures of Lilo and Nani Pelekai, two Hawaiian sisters, who must look out for one another after their parents die in an accident. Nani, the older sibling, becomes Lilo’s primary caretaker. To complicate things, the sisters are forced to adopt Stitch, an alien who crash-landed on Earth, as their pet. Throughout the film, the Lilo and Nani navigate their grief and adjust to their new family structure. Lilo and Stitch highlights the challenges that arise when life throws you curveballs, but also gives hope that family members can work together to overcome obstacles and create a new normal. According to Family Systems Theory, a family system is a collection of interdependent family members who seek to maintain a balance in overall family functioning. Each family member adopts a role (e.g., parent, child, sibling) based on the behavior they exhibit when interacting with other family members. These interactions can take place among subsystems of family members (e.g., parent-child, spouse-spouse, sibling-sibling) or among the family system as a whole. Key principles of Family Systems Theory (Smith & Hamon, 2017, Chapter 5): The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. The family system is not merely a collection of independent family members. Rather, family members are interdependent, and their interactions and experiences contribute to family functioning as a whole. Each member of the Pelekai family takes on an individual role (i.e., older sister/guardian, younger sister/dependent, and alien/pet). In addition to members as individuals, the network of relationships among Lilo, Nani, and Stitch (i.e., sister-sister, guardian-dependent, owner-pet) further constitutes their “family” unit. Individual and family behavior must be understood in context. Each individual is a cog in the machine of the family. Understanding an individual family member’s actions or behavior requires considering their needs, perspectives, or experiences. After losing their parents, Nani struggles to adapt to her new role as a parental figure and Lilo struggles to process the loss of her parents. The sisters’ individual stress influences their interactions with each another and leads to tension in their relationship. A family is a goal-seeking system. Family members work together to achieve common goals. These goals change as families grow and develop over time. At the threat of Lilo’s removal from Nani’s custody and placement into foster care, the sisters work to prove that Nani is a competent caretaker for Lilo. Families are self-regulating systems driven by feedback. Families respond to change through positive feedback loops (i.e., change that sustains or enhances) or negative feedback loops (i.e., change that causes fluctuations in family functioning). Though Stitch is initially a self-serving alien who creates chaos for the Pelekai sisters, Lilo’s repeated attempts at teaching Stitch kindness eventually lead the alien to understand the value of family love. Family systems seek to achieve equilibrium. In response to change, family systems look for stability and return to the status quo (i.e., equilibrium). Despite the wild adventures Lilo, Nani, and Stitch embark on throughout the film, in the end, their small family finds balance and creates a new normal. Family Systems Theory and Military Families Family Systems Theory emphasizes the importance of understanding the experiences of family members in the context of the family as a whole. This perspective of interdependence is particularly relevant for military families. For example, though Service members are deployed overseas and technically independent of their families, the at-home family members must respond to the stress and effects of deployment on their lives. Another example of familial interdependence is the lasting effects of trauma. Service members and Veterans who suffer traumatic experiences may develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD and its related symptoms (e.g., increased sensitivity, shorter temper) can alter how Service members and Veterans interact with their family members and it can affect their daily lives. Thus, just as a pebble tossed into a pond creates ripples regardless of the pebble’s size, individual experiences – military-specific or otherwise – have consequences for all family members, interactions among family members, and family functioning (Monk & Marini, 2022). Implications of Family Systems Theory for Military Families Family systems theory is a useful tool for military families to understand how to respond to stressful events. Here are some points your family can keep in mind moving forward: A family is a team. Think of each family member as a puzzle piece. Together, the pieces form a completed puzzle. One family member’s struggles can affect their relationships with and the well-being of other family members. Remembering that you are all on the same team and working together to support one another through family challenges (e.g., trauma, transition out of the military), can boost individual and family resilience. Instability doesn’t last forever. Change is normal, whether the result of stressful events (e.g., deployment) or common family transitions (e.g., parenthood, children leaving for college). Though changes can disrupt a family’s functioning, families have a natural tendency to return to stability. Like the pebble tossed into the pond, ripples will form – but, with time, they will also cease. In some cases, families can stabilize on their own by reevaluating their needs and collective goals and proceeding accordingly. Other times, families may be unsure how to overcome especially stressful circumstances on their own. Instead of a pebble, think of a boulder dropped into a pond. This time, the ripples are waves, and they may overturn your boat. During uncertain periods, seeking professional guidance (e.g., marriage and family therapy, mental health counseling) may help your family overcome stress and change and create a new normal. Communication is key. No one is a mind reader. When stress arises, family members need to communicate their needs. Doing so is easier when families establish clear communication plans and boundaries during periods of stability. Make it a habit to check in with one another and openly communicate your feelings. Ask what may be causing stress in your family members’ lives, so you’ll know when to be supportive. For example, when deployment looms, talk about what topics you will want to discuss during the deployment, how frequently you want to keep in touch, and which topics you want to wait to talk about until after the deployment.

THERAPY: WHERE DO I EVEN BEGIN?

Starting therapy – even thinking about it – can be overwhelming. How do I find a therapist? Do I want to do individual therapy, or family therapy? With my busy schedule, how will I find time to attend sessions? All of these are valid questions that come up for people about to begin their therapeutic journey. This article will guide you through the process by explaining words and phrases often seen in therapists’ online profiles, describing common provider types, offering suggestions for finding a provider, and describing what to expect when your sessions begin. In addition, we will debunk common therapy stereotypes. Therapeutic Words and Phrases on Profiles Two therapy-related terms you may see or hear on provider profiles (e.g., Psychology Today), are counseling and psychotherapy. Often, these terms are used interchangeably, but there are differences between the two. Counseling’s traditional focus is on a specific issue and its intention is to address a particular problem (e.g., stress management). Counseling can also include developing coping strategies or problem solving for different situations. By contrast, psychotherapy is a longer-term approach to therapy and dives deeper into the underlying processes of a person’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. Psychotherapy can address multiple problems simultaneously and is often used for diagnosis and the management of various mental health diagnoses, such as depression or anxiety (Sailing, 2021). You may also see providers mention theoretical orientation, which is how a therapist approaches their work and how they perceive their clients’ challenges (Sailing, 2021). For example, some theoretical orientations focus on early childhood experiences and relationships with parents, while others focus on the thoughts, behaviors, and emotions related to your current concerns. Theoretical orientations that you may see on profiles include Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), person-centered therapy, or a psychodynamic approach. Therapists who mention using a holistic perspective may adjust their approach based on the needs of a given client. Common Provider Types When searching for a therapist, it is important to understand the differences between the types of providers. Licensed Professional Counselors, Licensed Clinical Social Workers, Psychologists, Psychiatrists, and Marriage and Family Therapists can all provide therapy, but their training and overall approach may differ. Licensed Professional Counselors (LPC) and Licensed Clinical Social Workers (LCSW) are mental health professionals with at least a master’s degree in psychology, counseling, or social work. Upon graduation, they work in a clinical setting (e.g., counseling center) to accrue additional training focused on treatment, after which they take a licensing exam. LPCs and LCSWs are qualified to provide counseling to evaluate and treat mental health concerns for children and adults. Beyond this qualification, LCSWs also have the opportunity to engage in additional advanced training and receive their doctorate degree, at which point they become DCSWs (Doctor of Clinical Social Work). Psychologists have a doctoral degree in psychology focusing on the study of the mind and behavior. After graduate school they must complete a lengthy internship for additional training in treatment and theories. Psychologists can evaluate and treat mental illnesses through various assessments, clinical interviews, psychotherapy, and counseling. Based on their training and experience, psychologists can provide individual services to children and adults, or groups. A Psychiatrist is a medical doctor who specializes in the treatment of mental illnesses through the use of medications. Typically, the goal of seeing a psychiatrist is to understand and adjust medications and discuss how the medications are addressing symptoms. Often, psychiatrists do not conduct psychotherapy with their clients; instead, psychiatric visits are combined with sessions with a counselor or psychologist. Marriage and Family Therapists (MFT) earn a master’s degree to treat a wide range of clinical problems and specialize in work with couples and families. Their form of treatment is typically brief, solution-focused, and based on specific, attainable goals a couple can work to meet. The focus of an MFT’s psychotherapy is family systems – which can mean having family attending therapy together – and often addresses mental health within those systems. Suggestions for Finding a Provider Finding a provider or a therapy style that works for you is like test-driving a car, and you shouldn’t feel obliged to go with the first car you tested out. One way to find a provider is by reviewing profiles on websites like Psychology Today or Inclusive Therapist. Providers’ profiles will typically include the presenting concerns in which they specialize (e.g., children, LGBTQ+), their training, and even the insurance they accept. Another option for finding a therapist is to consult with family and friends who have been to therapy. Personal stories and referrals can be a great way to find the right therapist for you. Consulting with your medical provider, with whom you have an established relationship, is another way to find local providers in your area. It’s worth noting that sometimes a profile sounds great, but, once you officially meet, your connection with the therapist feels different. That’s okay! Feel empowered to take the time to find the best fit for you and your needs (just like test driving multiple cars!). What to Expect in Therapy Before attending your first therapy session, make sure to consult with your provider and ask about sliding scale rates and whether they accept your insurance. This way, you won’t have to worry about the cost of obtaining services and will know that your chosen provider is within your budget. Cost is often a barrier to attending therapy, so sorting out the issue beforehand may ease any feelings of stress or worry. It’s also important to ask about the structure of your appointments. For example, clarify how long sessions will last. Counseling and psychotherapy sessions typically last an hour unless a provider indicates otherwise. You might also inquire about the overall treatment length. The duration will vary, depending on your provider and your presenting concerns, but it’s important to understand how long you will be in therapy – whether several months or several years. And confirm whether your sessions will be in-person or virtual: discuss which would be best for your treatment and your schedule. During your first session, ask questions about the things that matter most to you in therapy. You may want to know how many years your therapist has been practicing, or their approach to someone with your concerns. The first session can also be a time to address values important for you to have recognized within the therapy setting. Common Myths about Therapy Something must be wrong with me if I need to attend therapy. People attend therapy for a variety of reasons, from managing daily life stressors (e.g., work-related stress, family relationships) to navigating severe mental illness (e.g., major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia). I will be judged by my therapist. For those who have never attended therapy before, one fear is that they will be judged when sharing vulnerable information. However, therapy is intended to be a safe space anyone willing to be vulnerable and authentic in their experiences. If anyone finds out I am going to therapy, I will be ruined. People will see me as weak. There is still a stigma around attending therapy, but it’s important to know that this service is confidential. Just like with any doctor’s visit, your attendance in therapy and what you share there stay within that space and are not something that will be shared unless you feel inclined to do so. Once I start therapy, I will be in therapy forever. The length of time that you attend can vary and depends on a variety of factors, including your presenting concerns and the form of therapy you choose. It’s also important to know that it may take time to see results – therapy is not an immediate process. All types of therapy are the same. Therapy can look different based on presenting concerns, the theoretical orientation of your provider, and the type of provider from whom you are seeking services. Therapy is a resource that is often underused due to unclear information on how to find a therapist, a lack of knowledge about the types of providers, and various myths that keep people from attending. Seeking therapy can be an individual, couple, or family choice, one centered on well-being and mental health. Remember that seeking therapy doesn’t mean you are weak. Instead, therapy gives you an opportunity for growth and additional support.

COPING STRATEGIES FOR MILITARY COUPLES: HOW TO FACE CONFLICT

Deployment is a major disruption in the lives of both the Service member and their partner, and adjusting to this new normal can take a toll on the relationship. Researchers have identified three common coping strategies used by couples to manage stressors during a deployment (i.e., avoidance, problem-focused, and emotion-focused) and evaluated how each strategy worked for the couples. We will discuss each method below. Emotion-Focused Coping Emotion-focused coping involves coping with the feelings related to the stressor rather than addressing the stressor directly. This strategy can be particularly helpful when dealing with the deployment stress because, while you cannot change the deployment, you can change the way you cope with it (e.g., go for a walk, bake a cake for your co-workers to take your mind off your partner being away). Researchers found that partners who use higher levels of emotion-focused coping and lower levels of avoidance coping during deployment report higher levels of relationship satisfaction. Problem-Solving Coping Problem-focused coping means trying to change the stressor itself. This strategy is most effective in situations where control is possible. Researchers found that when service members and their partners used problem-solving as a coping strategy during a deployment, it did not associate positively or negatively with their relationship satisfaction. Problem-focused coping is therefore unhelpful for cope specifically with a deployment. Avoidance Coping Avoidance coping is the management of conflict by not addressing the conflict directly. This can look like passive-aggressiveness, procrastination, or avoiding discussion of the issue. Sometimes, it’s easier to avoid a problem because it’s too difficult to face; however, avoidance coping strategies have the potential to make you angrier. Researchers found that avoidance coping was used most commonly by service members with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and by partners with psychological distress (i.e., anxiety, depression, and stress). However, in military couple relationships, both service members and their partners’ use of avoidance approaches resulted in lower relationship satisfaction and more psychological distress. It's important to remember that the most beneficial coping strategy is the one best-suited to each situation. Emotion-focused coping works great for managing stressors beyond your control, like a deployment. With that said, research has consistently shown that avoidance coping is linked to poor well-being. Although deployments are challenging for couples and families, spend time creating a plan that will allow you to maintain control of your relationship.

SEE THE CHANGE, BE THE CHANGE

Every February, the eating disorder community gathers to celebrate National Eating Disorder Awareness Week. This year’s theme is “See the Change, Be the Change.” Anyone, no matter their age, shape, or gender, can suffer from an eating disorder, and it’s the community’s goal to help society address that. One specific community goal is to draw attention to the fact that military families often suffer from eating disorders at a higher rate than the civilian population. One study of 46,219 Service members (72.6% male) evaluated disordered eating behaviors and weight changes over 2.7 years. When evaluating the onset of new disordered eating behaviors, about 415 women (3.3%) and 886 men (2.6%) reported an onset of disordered eating during that span. To analyze how these disordered eating behaviors affected weight changes, the researchers calculated the percentage of weight that subjects gained or lost over the course of the study. Researchers placed participants in one of five categories, depending on their percentage: Extreme weight loss (weight loss of 10% or more); Moderate weight loss (weight loss between 3-10%); Stable weight (remained with 3% gain or loss); Moderate weight gain (weight gain between 3-10%); or Extreme weight gain (a gain of 10% or more). Although 33.2% of women and 47.4% of men’s weight remained stable, 21.3% of women and 11% of men experienced either extreme weight loss or weight gain as a result of their disordered eating patterns. The authors did not further classify whether these Service members met the criteria for an eating disorder, but they did highlight how disordered eating behaviors are precursors to a diagnosable eating disorder. Children in military families are also at a higher risk of developing an eating disorder. In an additional study of 340 pairs of adolescent females and a military-affiliated parent (i.e., an active duty, deployed, or retired military family member), 21% of adolescents and 26% of parents met the criteria for an eating disorder. The study’s findings reflect the substantial overlap among children and military-affiliated parents who both have an eating disorder. The overlap was smaller in a civilian sample. One stressor comes from the constant changes required by military culture. Because active-duty Service members move roughly every four years, military children are required to change schools and make new friend groups. Sudden changes, such as a parent’s deployment or a permanent change of station, are also common. Children who lack control over their external surroundings may resort to either restricting food intake or overeating to cope with their emotions. With that being said, there are treatment options and resources for military families who may suffer from an eating disorder, like the National Eating Disorder Association (NEDA). Through NEDA, families can quickly be connected with a trained professional who can provide support through an online chat, phone call, or text. While not a diagnostic service, NEDA is a great way to learn about treatment options within the United States. And NEDA does offer guidance on specific questions to ask treatment providers, the different levels of care, and expectations for treatment. Additionally, TRICARE offers treatment at most inpatient and outpatient levels of care. Although recovering from an eating disorder is challenging, having the support of others makes a difference. Just knowing that someone supports you on your journey to recovery can increase the likelihood that you’ll seek and remain in treatment. And it’s always important to point out the prevalence of eating disorders within military families. If we want to see the change and be the change, we need to discuss the military community’s unique risk factors and make sure we’re offering the best treatment possible.

HELPING SCHOOL PERSONNEL PREVENT AND DE-ESCALATE PEER AGGRESSION: AN OVERVIEW OF EXISTING RESEARCH AND INSIGHTS INTO PROGRAMMING

Approximately 30-50% of students in the United States are aggressors or victims of peer aggression. Recently, the REACH team compiled the most up-to-date research on preventative programs designed to help adults in school and community-based settings to mitigate peer aggression (i.e., a person intending to harm another person of similar age, background, or social status). The focus of our report was to examine the existing literature on peer aggression and prevention programs so as to better understand the ‘best practices’ for mitigating aggression in education-based settings, and we synthesized how to address peer aggression through programming, how to prevent it through strategies and skills, and how to implement programs geared towards reducing it. Addressing Peer Aggression through Programmatic Efforts There are three main prevention approaches for programs focused on peer aggression for education-based settings: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Primary prevention programs aim to prevent or reduce peer aggression school-wide by implementing and promoting policies and skills (e.g., attitudes of empathy and problem solving, and relationship building). Secondary prevention programs are implemented when schools are beginning to observe early signs of peer aggression problems or if there have been ongoing peer aggression challenges; these programs tend to require more effort from the administrators and children. Tertiary prevention programs are implemented to reduce the frequency and severity of peer aggression while also mitigating the negative effects that have already occurred due to peer aggression; these programs are generally more intensive and target the needs of students who display negative outcomes due to peer aggression. Strategies to Prevent and De-Escalate Peer Aggression Research suggests several different factors and components may reduce peer aggression, including applying whole-school approaches that incorporate school-wide policies, effective disciplinary actions, and skill development of students and teachers. Whole-school approaches include aiming to prevent peer aggression on several levels (e.g., equipping school personnel, training students, engaging community members and families). Often whole-school approaches rely on creating school-wide policies, such as prohibiting certain behaviors (e.g., zero tolerance for threatening others), require teachers to report incidents of peer aggression (e.g., formal reporting policies), or create policies that promote and reinforce positive behaviors in students (e.g., ‘We are an accepting, inclusive school where we embrace our differences.’). Further, research suggests that discipline policies should incorporate fewer punitive strategies (e.g., detention, suspension) because this may actually increase aggressive behaviors and thus punitive discipline methods. Therefore, discipline policies should support aggressive children and help them learn different, positive behaviors (e.g., using words to express yourself, walk away instead of acting aggressively, tell a trusted adult your frustrations) rather than condemn them because this may exacerbate the aggression over time. Finally, whole-school approaches emphasize the importance of students’ and teachers’ skill development. More specifically, skill development focuses on teaching students’ skills that help them recognize peer aggression and manage peer aggression when it occurs. Some skills students could learn and apply include cognitive skills (i.e., alterative thinking), emotional skills (i.e., emotion regulation), and interpersonal skills (i.e., conflict resolution). Alternatively, teachers may learn how to better identify acts of peer aggression, debunking myths they have about peer aggression, as well as feeling more confident in their actions and utilizing empathy when responding to peer aggression. Considerations for Implementing Peer Aggression Programs Considerations should be made by school personnel before selecting and implementing programs for addressing peer aggression. Some of these considerations include school personnel buy-in and performing a needs assessment to evaluate the nature and scope of aggression occurring within the school. Effective program selection criteria include selecting a program that meets the unique needs of the school such as a prevention program or a school-wide program, selecting a program that is developmentally appropriate (e.g., preschool, elementary, or high school targeted program), and considering the amount of program engagement and/or program adaptability. To successfully implement a program, it is important to maintain a long-term focus on meeting program goals, properly train faculty and staff, and deliver the program as it was intended to be delivered. Finally, it is recommended that a program may be periodically evaluated to ensure it is addressing peer aggression and so modifications can be made if challenges arise. Read the Military REACH team’s full report on peer aggression and programming, Helping School Personnel Prevent and De-escalate Peer Aggression: An Overview of Existing Research and Insights into Programming, to access the citations used in this piece and to learn even more on the topic.

FAMILY SCIENCE 101: WHAT IT IS AND WHY IT MATTERS

Family Science 101: What It Is and Why It Matters By: Allison Tidwell Science refers to the systematic pursuit of knowledge related to phenomena of interest through observation, theoretical explanation, and experimentation. Although many people may think about the physical sciences (e.g., biology, chemistry) when they hear the term, science is applied in a wide variety of fields related to the human experience as well. Family science is one such discipline. Despite the extensive research conducted in family science, it is an underdiscussed field by the general public. As a team comprised primarily of family scientists, Military REACH is dedicated to sharing knowledge and insight from family research that focuses specifically on military families. So, let’s review what family science is and why it matters. What is Family Science? Born in the early 1900s, family science is the discipline in which scientific principles are applied to the study of families, interpersonal relationships, and the dynamic environments in which they interact. Family science draws upon many other disciplines (e.g., sociology, psychology, home economics) to capture a more holistic understanding of families’ lived experiences. According to the National Council on Family Relations, a professional organization focused on family research, practice, and education, there are five distinct characteristics that make family science a unique discipline. Family science is: 1. Focused on relationships between individuals, family groups, and their environmental contexts. 2. Strengths-oriented and focused on highlighting a family’s strengths so they can be sustainable and self-sufficient. 3. Preventative when addressing family issues by examining healthy family functioning. 4. Translation of research findings to practical applications. 5. Evidence-based through rigorous scientific research. The field of family science covers a wide variety of family-related topics. Some examples include: • Parenting and parent-child relationships • Romantic relationships and marriage • Human development • Early childhood care and education • Mental health, physical health, and well-being • Stressful life events, such as divorce or adverse childhood experiences • Military family functioning • Individual and family resilience Who are Family Scientists? Family scientists work to better understand family experiences and promote individual and family well-being. These scientists play a key role in furthering our knowledge of family related issues through observation and experimentation, but not every family scientist works in research. Family scientists also include those professionals who apply evidence-based interventions or counseling to families, educate family practitioners, and inform social policies. Examples of professional fields which stem from family science include family life education, marriage and family therapy, social work, family life coaching, and family policymaking. As mentioned before, Military REACH is a specific example of the work family scientists do, as most of our team is comprised of family scientists. Why does family science matter? As with any science, it is necessary to put what is learned into practice (Does this sound familiar? Putting research into practice is one of the main goals of Military REACH!). Family science research provides detailed insight into family adversities, risks, and protective factors related to these adversities, and how interactions between family members and their environmental context affect their well-being. This insight is particularly valuable to informing both practice and policy: Informing Practice • For helping professionals, family science research is used to develop and evaluate family services and programming. Evidence-based services or programs (i.e., those which are supported by research) are preferred when working with families because there is research to support their effectiveness in addressing the issue or concern. Further, once a program has been developed, studies can evaluate the efficacy of the program in achieving its targeted goals. If those goals are not met, helping professionals may then identify how to revise the program to better serve families. • Beyond program evaluation, research can also identify potential risk and protective factors for certain populations. Family scientists can then account for potential risk or protective factors to properly adapt the delivery of services to the unique needs of an individual or family. When reviewing and evaluating military family research publications, the Military REACH team identifies and encourages opportunities to incorporate key findings into family practice. Informing Policy • Scientific evidence is also valuable in the development, reform, and implementation of family-related policies at the local, state, and federal levels. When policymakers are informed about key family issues and family processes, they can better create policy solutions that address the needs of those most affected by the issue. Further, research on the effectiveness of a policy to solve an issue may indicate whether policy reform is required. Not all researchers provide in-depth policy recommendations related to their findings, so Military REACH and other mediating organizations identify and advocate for evidence-based family policy development and reform. Family science, although unfamiliar to some, offers valuable contributions to the livelihood and well-being of individuals and families. This field is continuously expanding our understanding of family experiences and will continue to inform how interventions and policies may best mitigate risks and bolster family strengths. To learn more about family science and key research topics in the field, you can visit the website of the National Council on Family Relations. References National Council on Family Relations (2021). About family science. https://www.ncfr.org/about/what-family-science National Council on Family Relations (2021). Key terms of family science identity. https://www.ncfr.org/about/what-family-science/key-terms National Council on Family Relations (2021). More about family science: History & name. https://www.ncfr.org/about/what-family-science/history-name#History Formatting Notes: *Okay, I’m no formatting goddess so I’m not sure this will be feasible, but I would love to have a section/column on one side of the page that has quotes from what family science means and why it matters from family scientists ourselves! The contents would include: Family scientists’ perspectives on the importance of family science research: “Family science is the study of people from conception to death – learning, researching, and understanding humans physically, mentally, emotionally, spiritually, and developmentally. It is so important because we all either (a) are a part of a family, and understanding our family members is important for cohesion and growth, or (b) if we do not identify as having a family, most people do work or interact with people who are part of a family. Therefore, understanding people, how they interact, why they do what they do, and most importantly what constructs/characteristics help us to be most successful and adaptive in life is important.– Haley S. “Family science is important because it is applicable to everyone; people are inherently relational and family science explores how healthy and unhealthy relational patterns influence human well-being. It is such a practical and universal topic!” – Ben B. *Here’s an image of what I think it could look like (or at least the general vibe):

YOU ARE NOT ALONE: NAVIGATING MENTAL HEALTH

Unfortunately, mental health stigma exists, and there is no exception within the military. The good news is that the stigma is starting to change, and people are beginning to view the importance of mental healthcare similarly to that of physical healthcare. For example, people are more encouraging and supportive than they previously were of seeing a therapist or taking medications to address mental health concerns. Also, there are more programs available to assist those who have mental health challenges, as well as programs for their families; however, there is still much work to be done to eliminate the stigma. This article discusses the impacts of mental health on the individual and their loved ones, available programs, lifestyle changes that can help mitigate mental health challenges, and lastly, suggestions when someone close to you is navigating mental health challenges. Impacts of Untreated Mental Health Concerns Mental health, for the purpose of this article, can be understood as the level of an individual’s psychological well-being or the absence of a mental illness. According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in 2017, one in five U.S. adults were living with a mental illness (46.6 million); therefore, if you are concerned about your mental health, you are not alone. What is important, is addressing mental health concerns as they arise. If mental health challenges are left untreated, they may lead to a wide variety of problems including: an increase in symptom severity, relationship problems with friends and family, unemployment, homelessness, poverty, and risk to the individual’s safety. So, it is important to recognize if you, or someone you know, is having a problem; take steps to address the problem and continuously monitor the status of your mental health. Impacts of Untreated Mental Health Concerns on Loved Ones When an individual is struggling with their mental well-being, whether that be depression, anxiety, or other mental health diagnoses, it also impacts their loved ones. This manifests itself in a few different ways: the spouses of individuals battling mental health may feel unable to or unsure of how to help their partner, and this can lead to feelings of helplessness, inadequacy, frustration, or even anger with their partner or themselves. Children also feel the emotions their parents carry, so if a parent is experiencing mental health concerns that have not been attended to, it could lead to the child exhibiting behavior problems such as aggressive outbursts or deliberately disobeying. Further, unaddressed mental health concerns could lead to marital distress. Research suggests that military couples were more likely to meet the criteria for major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance abuse or dependency, and suicidal ideation if they were experiencing marital distress. Therefore, addressing both relationship factors and mental health simultaneously is important and can be done by the couple meeting with a Marriage and Family Therapist. Programs Available to Address Mental Health Concerns The programs Independent but Not Alone and the VA Readjustment Counseling Service/Vet Center Program address both mental health concerns and also relationships of the individuals seeking treatment (i.e., family and friends). For example, the Vet Center provides services to families—not just Service members and Veterans—which foster a more holistic, familial approach in addressing mental health, and they are offered both online and in-person. Continue reading below to learn more about the programs. Independent but Not Alone VA Readjustment Counseling Service/Vet Center Program The Independent but Not Alone program is a web-based intervention for military spouses who need extra assistance managing the demands of military life. The program focuses on competence, autonomy, and relatedness (i.e., being able to relate your experiences to others). This 10-week, online program has been evaluated for its effectiveness and results are promising. Upon completing the program, participants reported higher levels of self-esteem and lower stress, anxiety, depression, and loneliness. Participants were placed in small groups with other military spouses also seeking mental health reprieve; therefore, this program might also provide an outlet for those struggling to connect with others who are in the same position as them. The VA Readjustment Counseling Service/Vet Center Program (henceforth known as the “Vet Center”) is comprehensive in that it provides counseling to eligible Veterans and active duty Service members including the National Guard and Reserve components, and their families. There is no cost affiliated with these services and no time limitation, meaning that there are unlimited sessions available to the Service member and their family. The aims of the Vet Center are twofold: to reduce the stigma around Veteran mental health and to increase the service utilization among Veterans with a mental illness. The Vet Center’s main areas of assistance are family counseling, and services for those who experienced combat trauma and military sexual trauma. Services are also provided to family members who have experienced the death of a Service member. Of note, Service members, Veterans, and their families do not need to be enrolled in VA healthcare, have a disability, or be connected to the VA or DoD to utilize Vet Center services. If these programs are not exactly what you or your family need, consider looking for other resources in your area that may suit you and your family better. This may mean finding an individual therapist for the family member experiencing mental health concerns or finding a family therapist to work with the family unit. Lifestyle Changes that Promote Improved Mental Health Research suggests that there are different lifestyle choices individuals can make to assist with their mental health struggles such as exercising regularly, drinking plenty of water, and eating a healthy, well-balanced diet. These are suggestions the whole family can participate in! Consider going for walks as a family, having a ‘water drinking contest’ to see who can drink the most ounces in a week, or cooking a healthy meal together. You should contact your doctor or physician if you continue to experience negative mental health symptoms upon implementing healthier lifestyle changes. When Your Loved One Struggles with their Mental Health When your loved one struggles with their mental health, it can be overwhelming. Encouraging him or her to seek help is not always easy; therefore, ask for help. Asking for help can look different for different people, but you might consider calling your primary care physician and explain what is happening, calling a friend who has been through something similar to what your loved one is going through, or just confiding in someone you trust so you feel less alone. It is also important to take time to make sure you, as a caregiver, are taking care of yourself by doing things you enjoy, such as exercising, gardening, spending time with friends, reading a book, or taking a bubble bath. Some signs that might suggest someone you love needs extra help include, but are not limited to: long-lasting sadness or irritability; extreme high and low moods; excessive fear, worry or anxiety; social withdrawing; and dramatic changes in eating or sleeping (either too much or not enough). I encourage you to seek help if you or someone in your family is struggling with mental health concerns and extend this help to others if they need support as well. You can do your part in decreasing the stigma associated with seeking mental health assistance by reacting positively when someone discloses that they are seeing a therapist or that they are taking medication, such as an anti-depressant. Also consider encouraging your friends/family to see a therapist if they are having difficulty with an issue they cannot manage alone—maybe that means driving them to their first appointment. Most importantly, respond and interact with people the way you would want them to respond and interact with you. Kindness goes much further than judgement! References: - https://aub.ie/MilitaryREACH-Whisman2020 o Whisman, M. A., Salinger, J. M., Labrecque, L., T., Gilmour, A. L., & Snyder, D. K. (2020). Couples in arms: Marital distress, psychopathology, and suicidal ideations in active-duty Army personnel. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129(3), 248-255. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/abn0000492 - https://aub.ie/MilitaryREACH-Mailey19 o Mailey, E. L., Irwin, B. C., Joyce, J. M., & Hsu, W. W. (2019). InDependent but not Alone: A web-based intervention to promote physical and mental health among military spouses. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 11, 562-583. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12168 - https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22918 o Botero, G., Jr., Rivera, N. I., Calloway, S. C., Ortiz, P. L., Edwards, E., Chae, J., & Geraci, J. C. (2020). A lifeline in the dark: Breaking through the stigma of veteran mental health and treating America’s combat veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 831–840. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22918

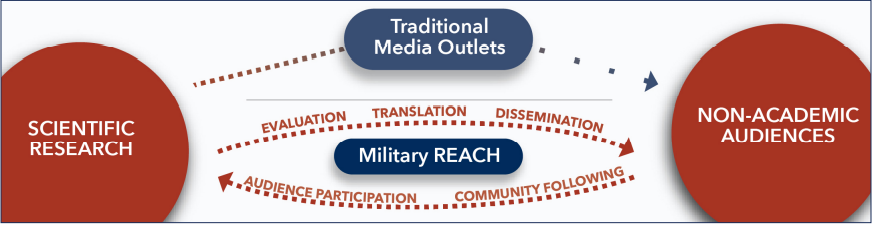

MOBILIZING FAMILY RESEARCH: AN OVERVIEW OF MILITARY REACH

The Military REACH team is dedicated to making research practical and accessible for individuals outside of academic settings who are interested in military families. To achieve this goal, our team follows a five-step process: identify, evaluate, translate, archive, and distribute. This process is a systematic approach to making research visible and available. First, we identify and closely examine current research publications related to our project’s focus area (i.e., military families) to determine how the information presented can best serve our target audiences: families, helping professionals, and policy makers. We utilize tools, such as PeerUS, and search engines, such as PsycINFO and Google Scholar, to effectively track new publications. Next, we evaluate the credibility and contribution of identified research studies using an evidence-based appraisal system, which has been modified to tailor the evaluation to the purpose of our project, the content of the research field, and the target audiences. This system assesses research on three aspects: credibility, contribution, and communicativeness. Thus, our evaluation assists readers with determining the degree of trustworthiness each publication possesses. After evaluation, we translate research articles into useful, practical, and high-quality resources. This step primarily involves the creation of Translating Research into Practice (TRIP) Reports, which are focused research summaries written to emphasize the implications for families, helping professionals, and policy makers. We then archive current research and original products into an intuitive, publicly accessible online library where users can find each publication’s detailed information, a link to its original source, and, when appropriate, a summary of the article. Finally, we distribute the research and resources to families, helping professionals, and policy makers through multiple social media platforms, electronic newsletters, and an online library. Our research team also partners with key stakeholders (specifically, the Department of Defense) to distribute these resources directly to those who can inform policy and practice. Military REACH serves as a bridge connecting the gap between academia and military families, helping professionals, and policy makers. The findings of research on military families have real, practical implications for service members, veterans, and their families, so it is imperative that our team work to make this information accessible and understandable to all. Through these processes, the impact of valuable research can be extended into the hands of the individuals who are wellpositioned to apply this information to inform intervention and prevention efforts at various levels.

Innovative Ways to Share Research and Create a More Scientifically Literate Community

The past year has been immensely challenging. As research is becoming more influential in public policy and behavior, there can be a compounding sense that we do not know what or who to believe. Across the past year, I have become increasingly convinced that the public, not just policy makers and scientists, needs to be scientifically literate. As it stands, there are several barriers to the public learning the necessary skills to evaluate and understand a standard research study on a topic of their interest. One such barrier is research being difficult to access due to the high cost to purchase research articles. Another barrier is the lack of technical knowledge needed to interpret statistical and scientific jargon. As scientific knowledge becomes increasingly more important to public life, the importance of developing and utilizing creative methods in disseminating knowledge is rising at a commensurate rate. Although traditional news outlets have a long history of discussing research, they often leave out important nuance in explaining scientific findings. This is especially the case when journalists are not trained in research terminology and general scientific practice. Therefore, knowledge shared directly between scientists and the public is vital to ensuring that research is accurately described by professionals trained in this discipline. However, that can still create problems if studies are not translated in approachable language. These goals are at the heart of projects like Military R EACH. R EACH seeks to evaluate, translate, and disseminate research so that families, helping professionals, and policy and military decision makers can be more informed. This is one of the reasons I am so proud to be a part of the work we do at Military REACH. Because of projects like REACH, non-academic audiences can get scientific knowledge that is accurate and easy to understand. However, this is not the only way to help create a more scientifically literate community. Increasingly, scientists are utilizing the Internet and social media to share knowledge. Researchers regularly post short excepts from recently published works on social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Clinicians utilize these sites to explain scientific findings with their followers. Additionally, avenues like YouTube are used to share entertaining and informative scientific presentations and trainings. These mediums create a direct channel between the producers and consumers of research. However, they are still limited in that the f low of information is restricted and unidirectional. Comments can be made on videos and social media posts but may not occur in real-time, which makes it difficult for researchers to respond to. As a result, communication methods that allow for live presentation and explanation of research while interacting with audiences may assist in the learning process more so than unidirectional methods. Live streaming is one such communication method. Sites like YouTube and Twitch allow for people to stream content of their choosing to their audiences and communities. Although generally used strictly for entertainment, there are numerous channels that generate and share scientific knowledge. Channels cover a wide range of topics from experiments to learning how to write computer code to discussing and explaining research articles. These channels allow communities and audiences can participate in live conversations with the broadcaster, asking questions or making comments for the streamer to respond to. It is an excellent method to stimulate conversation and scientific learning. These are some of the more innovative methods that scientists and practitioners are utilizing to share research and knowledge. It is my hope that even more innovative practices will be developed to increase the dissemination of research and cultivate scientific literacy in our communities.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CREDIBILITY IN RESEARCH DESIGN, IMPLEMENTATION, AND EVALUATION

In 1971, Philip Zimbardo and his team conducted the Stanford Prison Experiment to see what happens when ordinary people are put in an extraordinary situation. Eighteen college-aged men were randomly assigned a role: prison guard or inmate. The study examined the influence of the presumably evil prison environment, testing if simply being in the environment would turn typical people into harsh, power-abusing people. Shortly, the “guards” became cruel and even abusive to the “prisoners” to the extent that the study was shut down after six days (11 days early) due to the chaotic and traumatic nature of the experiment. The study is regarded as one of the most infamous scientific experiments in modern history. Despite being partially responsible for the establishment of ethical considerations in human sciences study, it is also a sterling example for why credibility should be evaluated when interpreting research. Credibility refers to how much a person can trust the findings of a research study, based on how carefully it was designed, implemented, and evaluated. A variety of areas should be considered when determining credibility, usually with emphasis on the study’s methodology. Methodology includes factors, such as the appropriateness of the study design, the representativeness of the sample, and the analytic approach. Credibility is important to evaluate because poor methodology can lead to poor results, which influence real life implications. Consider the Stanford Prison Experiment as an example. First, consider the recruitment process. The experiment recruited participants using a newspaper advertisement to request subjects for a “psychological study of prison life.” However harmless as this may sound, this phrasing could have attracted certain people to the study. In 2007, a study was conducted on sample selection that made two similar newspaper advertisements: one included information about being a prison study and the other did not. The ad that included the prison information yielded a sample of people with higher levels of aggressive and socially domineering personality traits than the ad without prison information. This suggests that Zimbardo’s sample may have been more aggressive than the average individual, potentially explaining the hostile behaviors observed in the experiment. Second, Zimbardo was a biased study participant, instead of an objective investigator. He posed as the prison superintendent and created an environment where the prisoners felt powerless and humiliated. The study team coached the participants and described the prison environment as “evil,” thus, calling into question the results that emerged. Imagine you are trying to measure taste preferences for a soda. Your test subjects try the drink, and then are only asked to list the things they didn’t like about the drink. The only data you will gather will be about people’s negative reactions because of the biased nature of the study’s design. In a similar way, the prison experiment was designed to produce abuses of power, and the results demonstrate that finding. Hopefully, at this point the argument for evaluating credibility is becoming clear. Because of the methodological issues of the study, the findings were skewed and lacked trustworthiness. Unfortunately, they were applied to influence real life implications. Shortly after the study, the results were used to influence Congressional prison reform policy and had an impact on the national narrative of prisons and human reality as a whole. The effects have been far reaching and all based on biased, highly questionable findings. Research is regularly utilized to inform local and national policy, as well as to inform practice; however, it can also be an illustration for the old saying: With great power, comes great responsibility (phrase commonly attributed to both FDR and Spider-Man). Researchers have the responsibility to produce sound science, and careful evaluation of research is necessary to ensure that findings are trustworthy. Without such rigor, the mistake could be costly for decades to come. Military REACH regularly summarizes and evaluates newly published research in, what we call, TRIP reports. Credibility is a key dimension of evaluation. See our library to understand how we measure credibility, and stay tuned in the coming months to learn about our other dimensions of evaluation - contributory and communicative.

SPEAKING “SCIENCE-ESE”: WHY CLEAR COMMUNICATION IS SO VITAL TO ACADEMIC WRITING

Imagine it: You are in a foreign country, surrounded by people who speak a different language. You are in a desperate rush to get somewhere; perhaps you’ve gotten lost on your way to a business meeting, or even worse, you need to find a bathroom! The people around you are well-meaning and would be glad to direct you, but you can’t understand a word they are saying! Despite their expertise and good intentions, their knowledge is lost in translation, and you are no closer to being where you want to be. This situation illustrates how knowledge and intent are irrelevant when severe communication barriers exist, which relates to the importance of clear communication in academic writing. Research is an incredibly useful way to understand the world. However, much of the time, the knowledge gained through research is lost in translation to “nonacademic” audiences. People who don’t know technical, scientific jargon can feel like the traveler in the story above when trying to read academic work: lost and confused despite the wealth of knowledge surrounding them. To avoid this confusion, clear communication should be the goal of every piece of academic writing. Therefore, articles reviewed by Military REACH are evaluated not only on scientific credibility and contribution, but also on how well the article communicates the topic or idea. The communicative aspect of an article is assessed by examining its coherence, understandability, and readability. First, an article is evaluated for coherence; in other words, how well it fits into the whole of scientific knowledge on the subject. Think of this like referencing a map in a mall: these maps have store locations, as a well as a “You are here” marker, to let you know your current position. Coherence is like the “You are here” dot on the map – it tells what is already known, what has yet to be discovered, and where the researcher is going next. The most coherent articles include information on previous research, as well as theoretical viewpoints, to help organize current knowledge on the topic of interest. Next, articles are examined for understandability. Put simply, how clearly and consistently are the authors using scientific or theoretical terms? Often, scientific findings and theories come with their own “jargon;” they may use language in non-typical ways or have specific meanings for certain concepts. The most understandable articles carefully define concepts and terms, providing concrete examples so that their readers can make mental connections to their own knowledge base. Finally, articles are evaluated on readability, which refers to clear, concise, and logically organized writing. Though this sounds simple and obvious, it may be the most difficult goal to achieve in academic writing. The most readable articles are clear by striking the right balance between scientific terms and plain language. If the article is too formal, people will have difficulty understanding it; if too informal, people will not take it seriously as a scientific work. Additionally, the bestwritten articles are concise, not using any more words than necessary to make their point while adequately providing context. Finally, the most readable articles have a logical flow to their content. The “story” of the paper is present, and the sections lead into one another with clear transitions. In this regard, writing an excellent scholarly work is an art form and difficult to accomplish. Though the Military REACH team places a high priority on scientific credibility (see more detail on this in the November 2018 newsletter) and contribution (see the January 2019 newsletter), the communicative nature of an article may be the most important piece for evaluation. Like the traveler in the story above, our audiences are not benefited by information that may as well be in a foreign language to them. Scientific writings are often criticized for being behind a knowledge wall, inaccessible to those who have not received extensive training in “science-ese.” It is vital that scientific writing be clearly communicated; otherwise, the findings could be the most helpful contribution that non-academic audiences will never hear.